1. Pauline Kael's review of Casualties of War. (1989) For my money, this lengthy New Yorker piece -- which I read and re-read for a solid hour in the magazine aisle of the SMU bookstore 17 years ago -- is the greatest one-off movie review ever written for a mainstream publication. It deserves that accolade for the sheer number of difficult things it does well.

1. Pauline Kael's review of Casualties of War. (1989) For my money, this lengthy New Yorker piece -- which I read and re-read for a solid hour in the magazine aisle of the SMU bookstore 17 years ago -- is the greatest one-off movie review ever written for a mainstream publication. It deserves that accolade for the sheer number of difficult things it does well.

First, it's a matchless example of Kael's enthusiasm, emotional engagement and conversational intimacy (three qualities that made her an important critic, and that are largely AWOL from even the most thoughtful American criticism being written now, too much of which is smug and/or pseudo-Olympian).

Second, it identifies what Kael thought was high water mark in director Brian De Palma's development as an artist and popular storyteller, and contextualizes it within his career.

Third, offers detailed descriptions of specific filmmaking choices, De Palma's possible motivation for making those choices, and their effect on her as an audience member (unusual for Kael; though she was brilliant at summarizing a film's narrative, its general temperament and its most significant subtexts, lines and performances, for some reason she often couldn't be bothered to write about specific shots, camera moves, cuts, sound cues or other visual/aural elements).

Fourth, it declares a moral and emotional kinship between the artist and the critic -- a hell of a brave and risky thing to do because it brings the critic down to the level of the nonprofessional moviegoer and opens her to charges that she's just reviewing her own feelings and not the movie (a favored tactic of those who disagree with an enthusiastic review of a particular film or filmmaker, but are too lazy to mount a detailed counter-argument).

This last part is crucial: what made Kael important -- so important that her persistent shortcomings seem trivial in comparison -- was her conviction that while there are objective criteria for judging a film's artistic worth, subjective responses should not be discounted, because they're the reason people go to movies in the first place -- and more importantly, they are stirred not by some random and inexplicable synapse firings within the moviegoer's brain, but by specific aesthetic choices made by the filmmaker. Analyze the technique and the response simultaneously, and you'll discover how the technique provokes the reponse in a particular viewer (though not in every viewer); make criticism personal and it will become universal. To that end, Kael's work was as much autobiography as criticism; it's part of the reason so much of her work remains compulsively readable (and in some cases more enjoyable than the movies she's writing about).

This last part is crucial: what made Kael important -- so important that her persistent shortcomings seem trivial in comparison -- was her conviction that while there are objective criteria for judging a film's artistic worth, subjective responses should not be discounted, because they're the reason people go to movies in the first place -- and more importantly, they are stirred not by some random and inexplicable synapse firings within the moviegoer's brain, but by specific aesthetic choices made by the filmmaker. Analyze the technique and the response simultaneously, and you'll discover how the technique provokes the reponse in a particular viewer (though not in every viewer); make criticism personal and it will become universal. To that end, Kael's work was as much autobiography as criticism; it's part of the reason so much of her work remains compulsively readable (and in some cases more enjoyable than the movies she's writing about).

Last but not least, here and elsewhere, Kael didn't cut De Palma special breaks because she happened to respond to his work. Unlike many of her present-day acolytes, she spanked directors who disappointed her. Her review of De Palma's Bonfire of the Vanities was tough and appropriately brief, and her review of The Untouchables made it clear that she thought De Palma was basically slumming for a paycheck, and subordinating his own vision to David Mamet's script, with its black-and-white morality and yahoo vigilante streak. And she was honest about what didn't work, even in movies she adored. Her Casualties of War review makes it clear that she thinks it's one of De Palma's masterworks, yet she still spends a section decrying how the script alters the original source material, a New Yorker article by Daniel Lang, to dummy-proof a message and make the soldiers' dialogue more faux-naturalistic. "Great movies are rarely perfect movies," she wrote of this one -- a quote that every critic should tattoo in reverse on his forehead so he has to read it in the bathroom mirror every morning.

Last but not least, here and elsewhere, Kael didn't cut De Palma special breaks because she happened to respond to his work. Unlike many of her present-day acolytes, she spanked directors who disappointed her. Her review of De Palma's Bonfire of the Vanities was tough and appropriately brief, and her review of The Untouchables made it clear that she thought De Palma was basically slumming for a paycheck, and subordinating his own vision to David Mamet's script, with its black-and-white morality and yahoo vigilante streak. And she was honest about what didn't work, even in movies she adored. Her Casualties of War review makes it clear that she thinks it's one of De Palma's masterworks, yet she still spends a section decrying how the script alters the original source material, a New Yorker article by Daniel Lang, to dummy-proof a message and make the soldiers' dialogue more faux-naturalistic. "Great movies are rarely perfect movies," she wrote of this one -- a quote that every critic should tattoo in reverse on his forehead so he has to read it in the bathroom mirror every morning.

From here on out, it's best to let Kael speak for herself. So here are two passages from that review, included in the 1992 anthology Movie Love:

"Trying to escape along a railway trestle high up against the wall of a canyon, Oanh might be a Kabuki ghost. She goes past suffering into the realm of myth, which in this movie has its own music--a recurring melody played on the pan flute...That lonely music keeps reminding us of the despoiled girl, of the incomprehensible language, the tunnels, the hidden meanings, the sorrow. Eriksson can't forgive himself for his failure to save Oahn. The picture shows us how daringly far he would have had to go to prevent what happened; he would have had to be lucky as well as brave. This is basically the theme that De Palma worked with in his finest movie up until now, the political fantasy Blow Out, in which the protagonist, played by John Travolta, also failed to save a young woman's life. We in the audience are put in the man's position: we're made to feel the awfulness of being ineffectual. This lifelike defeat is central to the movie. (One hot day on my first trip to New York City, I walked past a group of men on a tenement stoop. One of them in a sweaty sleeveless t-shirt, stood shouting at a screaming, weeping little boy perhaps eighteen months old. The man must have caught a glimpse of my stricken face because he called out, 'You don't like it, lady? Then how do you like this?' And he picked up a bottle of pink soda pop from the sidewalk and poured it on the baby's head. Wailing sounds, much louder than before, followed me down the street.)"

And lest you think Kael's serving up critic-flavored patter rather than real criticism, here's her superb, plain-language analysis of how De Palma's filmmaking choices illustrate his personality, philosophy and creative process -- particularly his use of dutch tilts, slow-motion and split focus compositions:"De Palma has mapped out every shot, yet the picture is alive and mysterious. When Meserve rapes Oanh, the horizon seems to twist into a crooked position; everything is bent away from us. Afterward, he goes outside in the rain and confronts Eriksson, who's standing guard. Meserve's relationship to the universe has changed; the images of nature have a different texture, and when he lifts his face to the sky you may think he's swapped souls with a werewolf. Eriksson is numb and demoralized, and the rain courses down his cheeks in slow motion. De Palma has such seductive, virtuosic control of film craft that he can express convulsions in the unconscious.

In the first half of the split-focus effect, Eriksson was so happy about having hit the grenade that he lost track of the enemy. In a later use of the split effect, Eriksson tries to save Oanh from execution by creating a gigantic diversion: he shoots his gun and draws enemy fire. What he doesn't know is that Clark, who is behind him, is stabbing her. He didn't know what was going on behind him after he was rescued from the tunnel, either. This is Vietnam, where you get fooled. It's also De Palmaland. Ther are more dimensions than you can keep track of, as the ant-farm shot tells you. And the protagonist who maps things out to protect the girl from the men (as Travolta did) will always be surprised. The theme has such personal meaning for the director that his technique -- his own mapping out of the scenes -- is itself a dramatization of the theme. His art is in controlling everything, but he still can't account for everything. He plans everything and discovers something more."

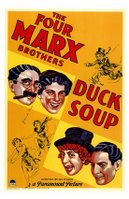

2. Joe Adamson's Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo. (1973) I made my parents buy this book from the Smithsonian Institition's gift shop during a sightseeing vacation to Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1983. I read it all the way back to Dallas and re-read it over the summer and into the fall; it's a deceptively great book; it's easy to imagine a casual reader enjoying it as showbiz biography and a fan appreciation without noticing what a sublime work of analysis it is. Adamson understands that "serious" and "humorless" aren't synonyms; where most books about the mechanics of comedy seem to have been written by the professorial equivalent of Margaret Dumont, this one is laugh-out-loud funny. And it hews to the anarchist vaudevillian spirit of its subjects, prefacing a detailed look at the dialogue-free mirror scene in Duck Soup with with a blank page that represents "ghostly, unreal silence," and noting that "...Horsefeathers' idea of college is all speakeasies, dog catchers and football, and its idea of a college professor must rank somewhere between Captain Hook and the Sherriff of Nottingham."

2. Joe Adamson's Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo. (1973) I made my parents buy this book from the Smithsonian Institition's gift shop during a sightseeing vacation to Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1983. I read it all the way back to Dallas and re-read it over the summer and into the fall; it's a deceptively great book; it's easy to imagine a casual reader enjoying it as showbiz biography and a fan appreciation without noticing what a sublime work of analysis it is. Adamson understands that "serious" and "humorless" aren't synonyms; where most books about the mechanics of comedy seem to have been written by the professorial equivalent of Margaret Dumont, this one is laugh-out-loud funny. And it hews to the anarchist vaudevillian spirit of its subjects, prefacing a detailed look at the dialogue-free mirror scene in Duck Soup with with a blank page that represents "ghostly, unreal silence," and noting that "...Horsefeathers' idea of college is all speakeasies, dog catchers and football, and its idea of a college professor must rank somewhere between Captain Hook and the Sherriff of Nottingham."

3. Vachel Lindsay's The Art of the Moving Picture. (1915) One of the earliest attempts to explain the aesthetic cause and intellectual/emotional effect of cinema, and still indispensible, particularly for anyone who didn't get Pauline Kael's memo and still judges movies as if they were novels or plays (or their descendant, the commercial linear narrative with a three-act structure). The associative interplay of images is paramount to Lindsay; everything else is mere garnish; sets, landscapes and props can be as expressive and as significant as any fact of characterization or performance, and rather than prove cinema's inferiority to other art forms, this fact confirms the medium's singular strengths. The Cabinet of Dr. Calgari, Lindsay writes, proves that "...the play is more important, technically, than in its subject matter and mood. It proves in a hundred new ways the resources of the film in making all the inanimate things which, on the spoken stage, cannot act at all, the leading actors in the films."

4. Agee on Film. (2000) James Agee's collected criticism for The Nation, Time and other publications is in many ways a forerunner of Kael's output -- equal parts film reviewing, history, journalism, social criticism and autobiography. Sometimes he dispensed with five to ten films in a single column, picking them off with a few lines each; other times he concentrated on two or three films; on certain occasions -- such as the release of Charlie Chaplin's Monseiur Verdoux and William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives -- he would return to the same movie for several weeks running, using his publication's bully pulpit to evangelize on behalf of a work he knew in his gut was a classic. (Armond White, Jonathan Rosenbaum and Stanley Kauffmann have all borrowed this tactic.)

4. Agee on Film. (2000) James Agee's collected criticism for The Nation, Time and other publications is in many ways a forerunner of Kael's output -- equal parts film reviewing, history, journalism, social criticism and autobiography. Sometimes he dispensed with five to ten films in a single column, picking them off with a few lines each; other times he concentrated on two or three films; on certain occasions -- such as the release of Charlie Chaplin's Monseiur Verdoux and William Wyler's The Best Years of Our Lives -- he would return to the same movie for several weeks running, using his publication's bully pulpit to evangelize on behalf of a work he knew in his gut was a classic. (Armond White, Jonathan Rosenbaum and Stanley Kauffmann have all borrowed this tactic.)

Agee didn't just analyze trends in subject matter or visual style; his specialty was unpacking the values (or lack of values) encoded in a motion picture, then judging them in relation to his own and highlighting the difference. The critic's humanism shines through in every paragraph, but one of my favorites is from his review of Shoeshine, which could be a mini-manifesto for artists hoping to produce movies that are honest about human behavior and the plight of the individual within society. "The heroes would presumably not have been destroyed unless they had been caught into an imposed predicament; but they are destroyed not by the predicament but by their inability under absolutely difficult circumstances to preserve faith and reason toward themselves and toward each other, and by their best traits and noblest needs as well as by their worst traits and ignoblest needs. Moreover, the film is in no way a despairing or 'defeatist' work, as some people feel it is. I have seldom seen the more ardent and virile of the rational and Christian values more firmly defended, or the effects of their absence or misuse more pitifully and terribly demonstrated."

5. Durgnat on Film. (1976) For more, click here.

TO READ THE FULL POST WITH COMMENTS, CLICK HERE

5. Filmmaker Don McKellar’s review of the E.T. re-release in The Village Voice showed me how a cheap, snide, glancing, dismissive review of a beloved American classic… can also be right.

5. Filmmaker Don McKellar’s review of the E.T. re-release in The Village Voice showed me how a cheap, snide, glancing, dismissive review of a beloved American classic… can also be right. 4. James Baldwin’s book The Devil Finds Work put everything that infuriates me about classical Hollywood into a handful of scalding essays, and a simple concept: White supremacy is at the core of even Ho'wood's gushiest liberal projects. (I want to dig him up so he can write something on Crash.)

4. James Baldwin’s book The Devil Finds Work put everything that infuriates me about classical Hollywood into a handful of scalding essays, and a simple concept: White supremacy is at the core of even Ho'wood's gushiest liberal projects. (I want to dig him up so he can write something on Crash.) 2. Armond White’s dis review of Malcolm X in a 1992 issue of the long-gone radical black newspaper The City Sun knocked me to the floor. I was a black kid reading a black writer eviscerating The Black Movie of the Decade in a black newspaper. Balls. And White pinpointed a disappointment with the film I hadn't been able to articulate. He decried Spike’s heavy-handed “look-at-me tropes,” like the shot of those dastardly Klansmen riding off against a moon backdrop. The X review and the bizarre spectacle of full-page Antonioni analysis in a paper read in Harlem barbershops converted me to Whiteism as swiftly as Malcolm succumbed to Islam. After that, I had to read everything this crazy negro had to say. And I learned a hell of a lot.

2. Armond White’s dis review of Malcolm X in a 1992 issue of the long-gone radical black newspaper The City Sun knocked me to the floor. I was a black kid reading a black writer eviscerating The Black Movie of the Decade in a black newspaper. Balls. And White pinpointed a disappointment with the film I hadn't been able to articulate. He decried Spike’s heavy-handed “look-at-me tropes,” like the shot of those dastardly Klansmen riding off against a moon backdrop. The X review and the bizarre spectacle of full-page Antonioni analysis in a paper read in Harlem barbershops converted me to Whiteism as swiftly as Malcolm succumbed to Islam. After that, I had to read everything this crazy negro had to say. And I learned a hell of a lot.